There is no reflection of home in the pine while there is still no comfort in the forest.These wind swept coasts may cool our heads, embrace us and house us but they do not forget. Scratch the surface and history remains. Six inches below chemical fuelled top soil, the embers still glow.

In a time of ecological upheaval and social reflection, Remnants explores the intersections of Pākehā identity, ecology, and the journey toward reconciliation in Aotearoa. Holly Walker, Will Bennett and George Turner each present distinct practices which are unified by a shared commitment to interrogating what it means to inhabit these lands as Pākehā and to navigate the complexities of belonging in a place with the open wounds of a colonial past.

Remnants aims to show Pākehā the need to embrace their identity. Through cultural motifs, reimaginings and satire, Remnants presents a case to welcome our collective pasts and not escape it. The exhibition intends to encourage Pākehā to understand the weight of history, recognize privilege, and accept responsibility. As Aotearoa faces an urgent call to address both environmental degradation and the legacies of colonisation, the role of Pākehā must be one of empathy; it necessitates active engagement, a commitment to listening, and a willingness to learn. How do we reconcile with the past while nurturing a future that respects and upholds Te Tiriti o Waitangi and the rights of tangata whenua? Remnants poses this critical question, encouraging reflection on what it means to be Pākehā today.

The remnants of colonialism continue to shape contemporary Pākehā identity in Aotearoa, embedding layers of inherited privilege, cultural disconnection, and a complex relationship with the land and its original peoples. These remnants manifest in both visible structures—like laws, property rights, and social hierarchies—and in the less tangible, yet pervasive, narratives that frame Pākehā belonging and power. There are also physical remnants such as the litter of brick, steel and now plastic that is scattered throughout Aotearoa. As Pākehā, we must acknowledge our shared histories, understand the trauma and consequences of colonisation, and recognise the privileges that come with it. It is about seeking ways to contribute positively to the collective well-being of all who call Aotearoa home, particularly Māori, by honouring their knowledge, tikanga, and sovereignty.

Remnants explores a pathway toward this through the act of reconnecting with our ancestors and reclaiming and reimaging the remnants of our past. By understanding our own whakapapa and the historical contexts that shaped our presence here, we can confront the often uncomfortable truths of our past and use this knowledge to foster a more just and sustainable future. Walker, Bennett and Turner invite viewers to reflect on their own identities and responsibilities, to question, to unlearn, and to relearn.

Together, their works offer a vision of Pākehā which is informed by a respect for the land, an understanding of shared histories, and a commitment to co-creating a future that honours the diverse narratives of Aotearoa. It is a call to reconnect—with the land, with each other, and with the past—in order to create a more equitable future.

Essay Written by George Turner.

The works

Standing stones:

In my making I try to only use what is already here, or rather, what has been left behind. A reminder, legacy or marker of settler colonialism, a piece of my history. These concrete blocks are rubble extracted from the ground earlier this year. Made to be foundations of a Wellington home, built in 1906, which is now once again a ‘construction site’. This work considers processes of ‘re’construction and ‘de’construction, in relation to the violent legacy of colonialism on the environment and history. Coincidentally, 1906 was the year former Prime Minister of New Zealand Richard Seddon died. Seddon was a misogynistic imperialist who was also appointed to several portfolios, including Minister of Public Works – ‘construction’ and ‘development’. The concrete standing stones, or as I have been referring to them, the ‘white trash’, materially represent an intention of permanence or longstanding occupation.

In this offering, I view the ‘stones’ extraction as an opportunity to reimagine the legacy of remains and waste. In their materiality and stature I see a naive distant relation to my ancestors' familiar standing stones in Ireland, England and Scotland. The symbols carved into these stones are humble articulations of lessons and realisations I have collected and that my tangata Tiriti community have embodied in the process of becoming consciously Pākehā, as well as some aspirational dreaming’s for this cultural identity. These lessons and the name of each standing stone includes: Be in love with all of my friends, There is no loss in sharing your own privilege, Reciprocity restores balance, Nurturers of memories and harvesters of truths, Guardians of animals, lovers of rivers, worshippers of the moon, bodies of water. Each stone has been carved using a greywacke toki (adze). Greywacke is an extremely solid sandstone found in Aotearoa, England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. We are from the same places.

Toki: It makes sense that these tools, this kōhatu that I used to reveal the articulations of my Pākehātanga, moved through the hands of Māori and were informed by Mātauranga Māori in some way. Living as Pākehā means living in relation to Māori and acknowledging how that has shaped our world view. These toki are made from greywacke sandstone gathered from Hue te Para. I was advised and mentored by pounamu carver Emry Kamahi Tahatai Kereru (Waitaha, Kati Mamoe, Rakiamoa, Atawhiua, Tuahiri, Te Uri Kopura, Ngati Hao, Ngati Whatua Tuturu, Ngati Kahu, Te Patuharakeke). Emry offered me so much knowledge surrounding which stones to use, where to find them and invited me to his whare to carve them into a rough collection of toki. The standing stones were carved using these tools, they aren’t too fancy, but they embody the exchange of learning, whakapapa, and reimagining collaborative futures.

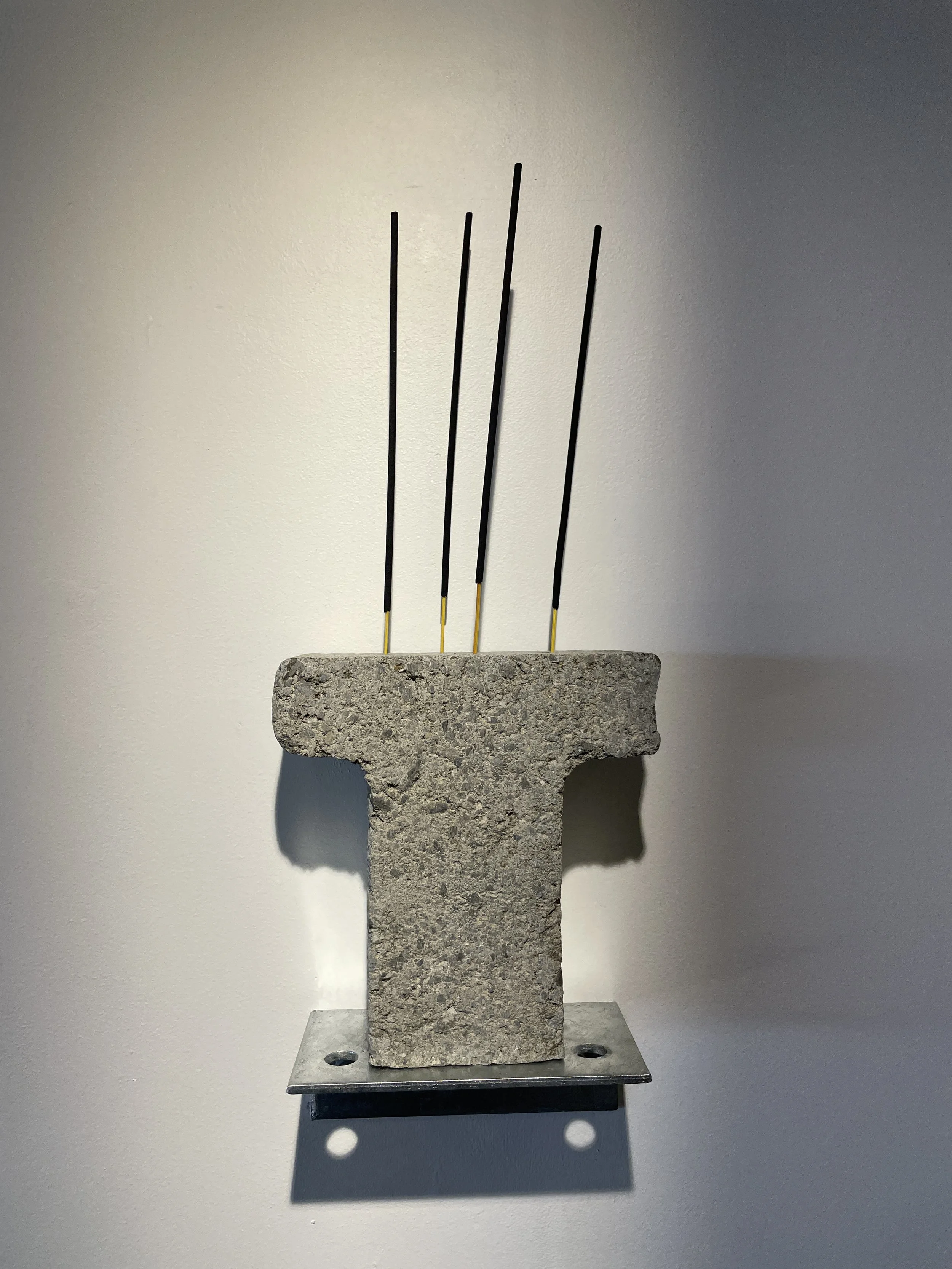

Candle sticks: Made from industrial waste, the concrete ‘I’ is a small part of a grid foundation called a crib wall. Many of these ‘I’s, all interlocked, hold the earth together underneath buildings; or creating walls where streets cut through hills. In isolation they cannot fulfill this purpose and become lone standing stones. The ‘I’ candlesticks mimic the materiality and ritual of memorialisation. The ‘I’ represents the individualism, the isolation, the loneliness, the monolithic understanding of history that capitalism and colonialism grooms us into. This candle stick acknowledges the need for community through contemplating the symbology of the ‘I’ while also acknowledging stories of individuals and moments that have been overshadowed, erased, oppressed, retold or untold.

They memorialise the history they want us to remember. In the settler colonial state of new zealand often the people or events that have been memorialised in statue, are colonisers, war heroes/criminals and other elitist colonial conquests. To honor their bravery and achievements historically we have erected vague phallic shaped stones, concrete and metals. This work contemplates this legacy and danger of representing one dominant narrative.

Like my ancestors, the candle is lit to set intention, bring to light, sever ties, bind souls and reconnect. Here’s to the death of individualism and the rebirth of community!

Incense holder: Made from industrial waste, concrete foundation piece of a crib wall. This incense holder reflects the constellation of Te Pae Māhutonga (the southern cross) inspired by ancient rock forms of Ireland named bullauns. Sacred ritual sites whose purpose is still not exactly known.

Remnants

Hunters and Collectors Gallery. 2024. Exhibition with Will Bennett and George Turner.