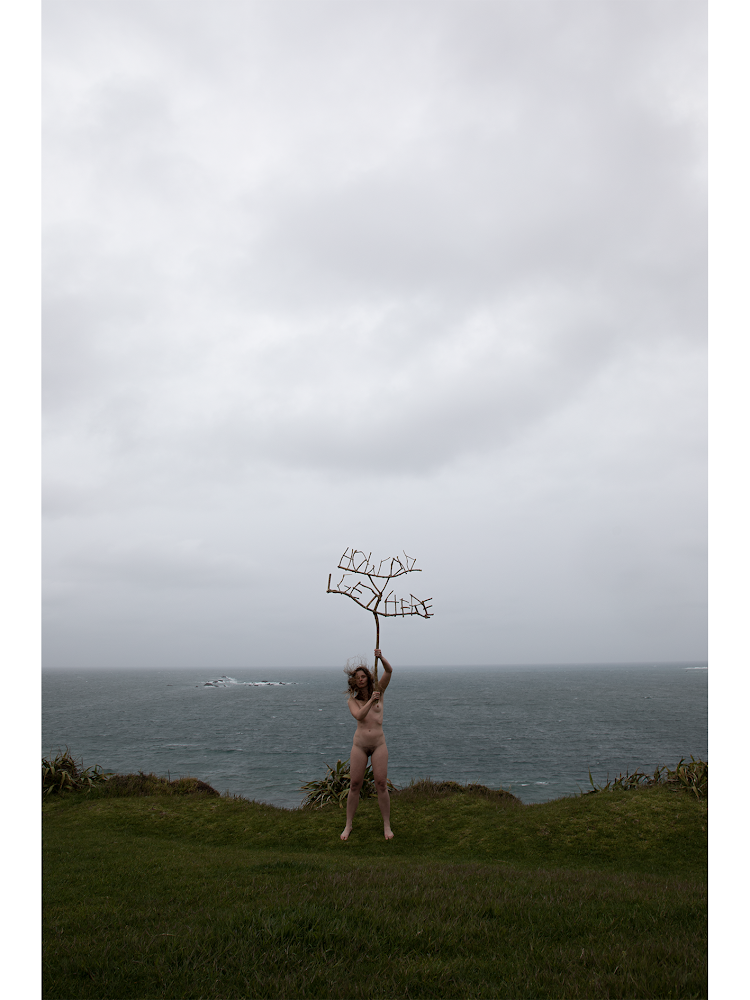

HOW DID I GET HERE

Notes: Gorse and European Pākehā share similar characteristics of imperialism in Aotearoa. I have previously explored this relativity in projects in contrast to indigenous Māori plants, in collaboration with Māori artist and best kare, Ana McAllister. In this project, the whenua is Papatuanuku, and I am the contrasting subject being the identity politics of both gorse and Pākehā - unsettled settler. HOW DID I GET HERE evolved out of a discussion I had with a class of undergraduates discussing Pākehā identity. The focus of this discussion was helping Pākehā students understand that to contribute to decolonisation, rather than centring the ways Māori work to decolonise, and depending on Māori to educate them on their history, Pākehā need to centre their research in their own white identities, histories and relationship to colonisation. This will contribute to Pākehā understanding their location in Aotearoa.

This discussion was initially met with the usual silent tension, a space where a sense of guilt and confusion is battling with intrigue. After some assurance that the space was safe and that all thoughts would be considered as subjects to critique and investigate together, the students began to lightly share some points of view. A lot of their contributions where linked to simply never knowing or considering their whiteness, or not having any interest in the politics of their whiteness.This discussion brought awareness to the way inherited whiteness serves their privilege and operates silently for them; while simultaneously hurting our Te Tiriti partners and other ethnically marginalised groups.

It used to surprise me how little Pākehā knew of their own identity and history, while also knowing little to nothing of Māori history. The factor that still surprises me is while missing both of these cultural identifiers that make up a Pākehā identity, some Pākehā still don't feel a need to understand or research their heritage and how they came to be in Aotearoa. This I believe is due to how privilege operates, dangerously, like a gas leak.

‘HOW DID I GET HERE’ speaks to me of the naivety and existentialism I sensed in this class, and have felt in my own body in cycles.

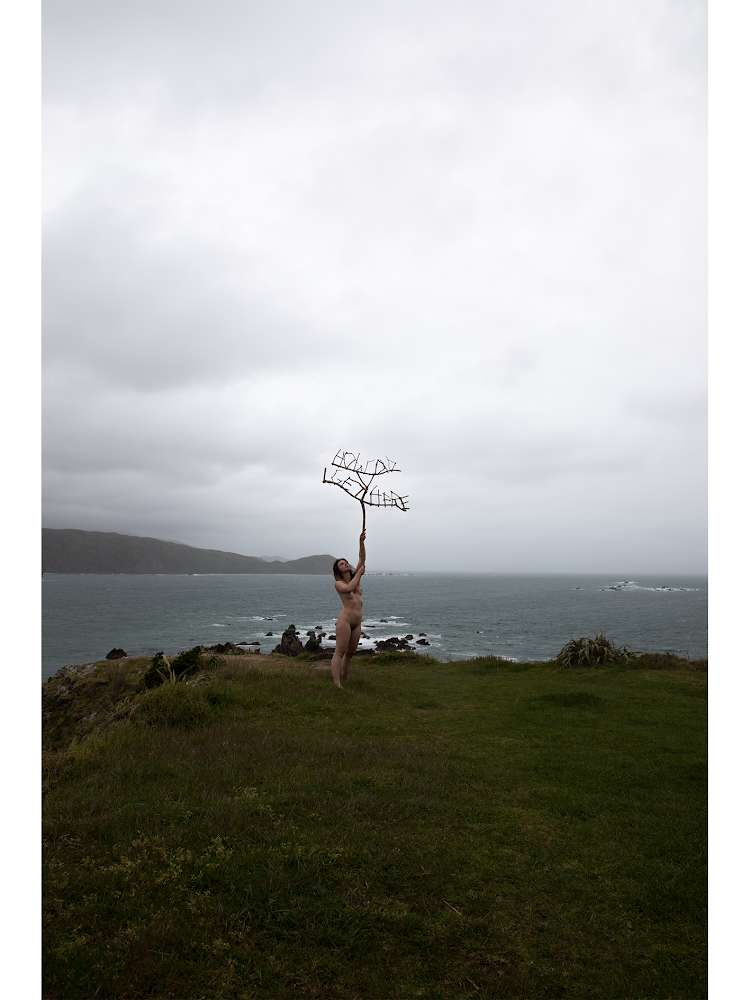

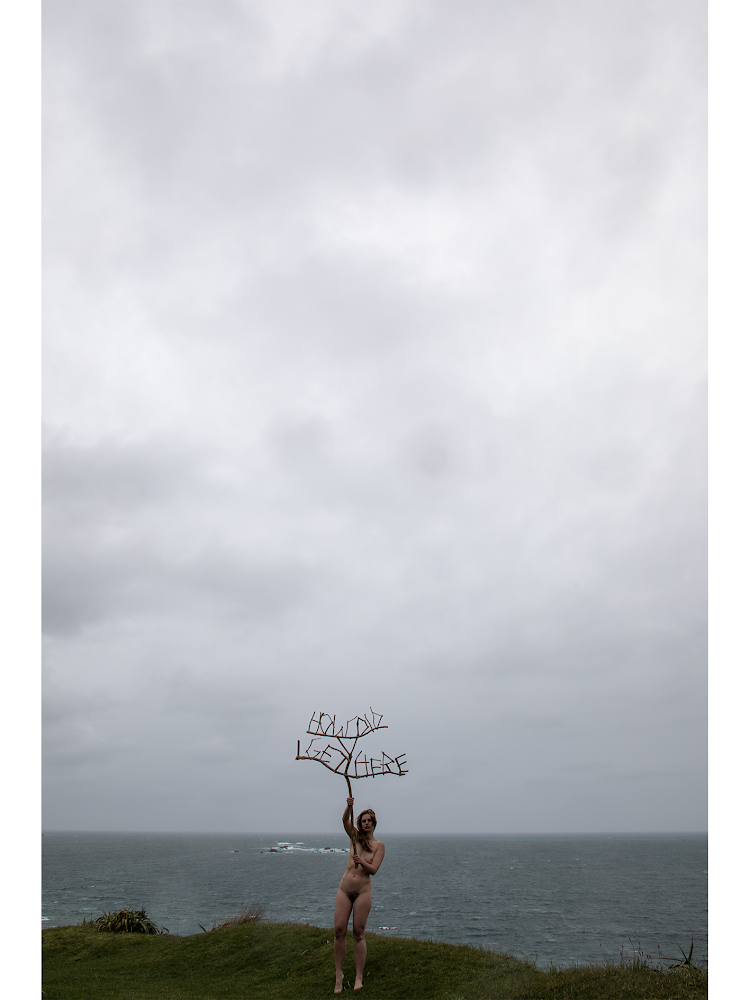

My white, able, cis-female body pictured at the centre but in distinct contrast to the desolate and seemingly untouched image of Aotearoa. This imagery relates to early western renaissance (propaganda) paintings, where there are often idealised white women depicted in nature. A pure paradise, a virgin landscape of evergreen and endless providing. The type of western thinking that has been and continues to kill the environment.

I imagine this work in a western posthuman context, where my body has previously existed in a locus space somewhere where Pākehā have no memory of their ancestors terrorisms of journeys and no idea of indigenous peoples existence, where they have never questioned or have had to question anything of themself.

Similar to the experience of being a white student studying in western institutions.

My body is then pulled through a void from my mother land to this other land and I am birthed out on to Aotearoa. The void closes and I am left in this landscape.

This image is taken on seatown heights, right on the edge on the peninsula. From where I was standing looking back up toward more land, where I could see the Te Whetu Kairangi pā site. “The pa was named Te Whetu Kairangi, because its inhabitants saw no other tribes, and dwelt with a view only of the stars at night.” The parallel between ‘seeing no other inhabitants’ related well in a paradoxical way to the Pākehā position the work deals with. -i dont belive in coincidences, therefore acknowledge the invisible ropes that pulled me to this site.

While standing there with my sign. in the wind. Hair all over my face. In the nude, I at first felt as if I were doing something disrespectful, obstructing the pā’s view to the sky and the sea. I looked at the po planted deep in the whenua and the eyes of the whakaaro looking past me, while I struggled to ground my feet while being blown all over the show. I had earlier considered planting my stick in the ground , but I knew, sometimes you do just know, that that would be wrong or not tika. I would leave this site with no trace of my being there.

While I was asking myself, what felt to be a deep philosophically personal question of identity, ‘how did i get here’

I felt as if the whakairo were laughing at me, chuckling at my naivety and desperateness for something they have and have known from the beginning. They were planted, wise like old trees.

This experience changed the energy of this image for me to something much more playful and perhaps ironic, satire. Although I do really insist on the importance of Pākehā answering this question of how did I get here, there is a level of “you’ve got to be kidding me” “here we go again” I get from this image, I could imagine Māori sympathising with.

As you can see, there is not question mark at the end of this… question… this is intentional as often this is just a statement, a curiosity not often committed to. I enjoyed the stagnancy or even audacity of this choice.

On reflection of these images I started to consider whether ‘how did i get here’ was the right set of words to construct, maybe ‘where did i come from’ could be a more conducive question, a question Pākehā actively avoid. Since this work I have asked Pākehā, ‘ how did you get here?’ and the answer is ‘I was born here.’ Nothing before, fresh from the void.

Images taken by Ngaurupa Fyson Davis. 2020